This section is based on the 2022 thematic report and has not been updated since.

Acute health problems like infections typically appear suddenly, then disappear spontaneously or through an effective treatment, generally (with some exceptions) within a fairly limited time span. Chronic conditions, on the other hand, tend to develop more gradually and last for longer periods. The Belgian Observatory of Chronic Diseases of RIZIV-INAMI (National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance) defines them as “diseases that last at least 6 months”.

Chronic diseases are often the result of multiple causes and can’t always be cured; more often than not, the aim of treatments and other healthcare interventions will be to keep them in check, i.e. to keep symptoms under control, avoid flare-ups and, if possible, to prevent the person’s health from getting worse over time. This will often require complex and multidisciplinary care.

Needless to say, chronic diseases can have far-reaching implications for patients, as they can impact not just their health but also their job, their hobbies, their daily routine and every aspect of their life. They also entail major costs for the health insurance system, for society as a whole and of course for the patients themselves.

A KCE study published in 2022 selected 27 indicators that were deemed particularly relevant for people living with chronic conditions and assessed them specifically for this subgroup of patients and for the general population.

This section retains the four indicators that are specific to people living with chronic conditions, which relate to the percentage of the population living with one or more chronic diseases (CHR-1, CHR-2, CHR-3) and to their self-reported quality of life (QoL-1).

Thirteen other indicators included in the 2022 study have been updated in the latest evaluation of the performance of the Belgian healthcare system (HSPA 2024), but only for the general population. More detailed information on these indicators can be found in the corresponding sections. However, we also chose to keep the sub-analyses of these indicators according to the chronic status of the patient, which are briefly presented below; the results for this subgroup are still based on the 2022 study. This applies to the following indicators:

- Accessibility of care indicators: share of out-of-pocket (OOP) payments in total healthcare expenses (A-2), percentage of households facing catastrophic or further impoverishing OOP expenses (A-4, ex-EQ-4 and EQ-5), percentage of people with self-reported unmet needs for medical care due to financial reasons (A-6, ex-A-4).

- Continuity of care indicators (subdimension of quality of care): global medical record coverage (QC-1), percentage of patients who see a GP within a week after leaving the hospital (QC-3) and the percentage of eligible patients who have a reference pharmacist (QC-7).

- People-centredness indicators (subdimension of quality of care): patients’ experiences with their physicians (QP-1, QP-3, QP-4).

- Preventive care indicators: influenza vaccination among the elderly (P-4), breast cancer screening (P-6, P-7), regular contacts with a dentist (P-11).

A few other indicators directly relating to people living with chronic conditions have been updated in HSPA 2024 and moved to other (sub)dimensions (where you will find the latest results):

- Under effectiveness of care (subdimension of quality of care), the indicators on preventable hospital admissions for three chronic diseases – asthma (QE-1), COPD (QE-10) and (complications of) diabetes (QE-2) –, and the successful treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis (QE-11).

- Under appropriateness of care (subdimension of quality of care), the indicators on the appropriate follow-up of diabetes in patients aged 18 years or over, receiving insulin (QA-1) or receiving glucose-lowering drugs other than insulin (QA-2).

- Under continuity of care (subdimension of quality of care), the indicators on the percentage of adults living with diabetes (receiving insulin or receiving glucose-lowering drugs other than insulin) enrolled in an official follow-up initiative (convention/diabetes passport/care trajectory) (QC-4, QC-5).

- Under efficiency, the indicator on the use of low-care dialysis (E-5).

Contextual indicators

| Population group | Score | Year | BE | Fla | Wal | Bru | Source | UE-15 mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR-1 Proportion of people with the RIZIV – INAMI chronic illness status according to their official health expenditure | ||||||||

| In the entire population | C | 2018 (2020) |

11.3 (12.1) |

11.3 (12.1) |

12.0 (12.9) |

8.7 (9.4) |

IMA-AIM | - |

| In subpopulation with self-reported chronic disease | 2018 | 31.5 | 32.9 | 29.6 | 31.0 | HISLink | ||

| In subpopulation with self-reported multimorbidity | 2018 | 39.2 | 42.0 | 43.5 | 35.6 | HISLink | ||

| CHR-2 Proportion of people reporting a chronic disease | ||||||||

| In the entire population | C | 2018 | 29.3 | 27.6 | 32.7 | 28.7 | HIS | 36.6 |

| In subpopulation with RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | 72.1 | 71.7 | 74.8 | 70.8 | HISLink | |||

| CHR-3 Proportion of people reporting multimorbid state in the last 12 months | ||||||||

| In the entire population | C | 2018 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 10.8 | HIS | - |

| In subpopulation with RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | 47.4 | 48.3 | 48.2 | 38.3 | HISLink | |||

| In subpopulation with self-reported chronic disease | 33.8 | 34.4 | 34.1 | 28.7 | HIS | |||

| QOL-1 Self-perceived quality of life* | ||||||||

| In the entire population | C | 2018 | 0.843 | 0.868 | 0.798 | 0.839 | HIS | - |

| In subpopulation with RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | ⚠️0.630 | 0.671 | 0.558 | 0.627 | HISLink | |||

| In the subpopulation with self-reported chronic disease | ⚠️0.696 | 0.739 | 0.632 | 0.687 | HIS | |||

Percentage of the population granted the RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status (CHR-1)

Introduced in 2013, the RIZIV/INAMI “chronically ill” patient status is granted automatically to all patients who reach or exceed a certain threshold of official health expenditures (€300 per quarter in 2013, €365.18 in 2023) during at least 8 consecutive quarters or are entitled to the lump sum for the chronically ill. It stays valid for 2 years (5 years for people with rare diseases) and gives patients access to a lower yearly cap on their co-payments within the maximum billing system (Maximumfactuur/Maximum à Facturer or MaF).

The percentage of the population entitled to this status provides information about how well the Belgian healthcare system protects people with chronic diseases against high healthcare costs.

Results

- The overall percentage of the population granted the RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status has been increasing from 8.7% in 2013 to 12.1% in 2020. This trend was similar in all three regions.

- The percentage of people with this status was highest in Wallonia, followed by Flanders, then Brussels. However, figures varied considerably between provinces.

- In all three regions, considerably more women than men have been granted the “chronic disease” status.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Percentage of people with a self-reported chronic condition based on the Health Interview Survey (CHR-2)

A financial protection mechanism like the official RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status does not precisely reflect the actual number of people living with a chronic condition because some people living with chronic conditions may not have chronic health expenses. Conversely, some people who are not living with a chronic disease may have chronic healthcare expenses. The percentage of people who reported having a chronic condition in the

National Health Interview Survey (HIS) offers complementary information on how common this type of issue actually is in Belgium.

Results

- The overall percentage of people with a self-reported chronic condition increased from 25.1% in 2001 to 29.3% in 2018. In 2018, this percentage was highest in Wallonia (32.7%, vs 28.7% in Brussels and 27.6% in Flanders).

- The percentage of the population with a self-reported chronic condition increases with age, from 14.1% in 15–24-year-olds to 44.1% in people aged 75 and older.

- European data (EU-SILC, European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions) show that the proportion of people living with a chronic in Belgium is low compared to the EU-15 average. In 2020, the prevalence rate was 24.8% in Belgium versus 34.1% for the EU-15 average.

- There is a substantial gap between the percentage of people with a self-reported chronic condition and the percentage of people with an official RIZIV-INAMI “chronic disease” status – 29.5% vs 12.9% in 2018, a 16.6% difference.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Percentage of people who self-reported several chronic conditions in the Health Interview Survey (CHR-3)

Chronic diseases often occur together because they are partly influenced by the same underlying causes (like e.g. lifestyle and living conditions); people with diabetes, for instance, are also more likely than others to have a heart condition. This co-occurrence of several chronic diseases is known as multimorbidity. This indicator gives us an idea of the health status of the population, but also of healthcare needs.

Results

- The percentage of people reporting at least two chronic conditions has increased between 2001 (11.4%) and 2018 (15.2%).

- Unsurprisingly, multimorbidity figures increase with age, from 0.8% in the 15-24 age group to 41.8% among people aged 75 and over in 2018.

- In 2018, the percentage of people with self-reported multimorbidity was highest in Wallonia (16.5%, vs 15.1% in Flanders and 10.8% in Brussels).

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

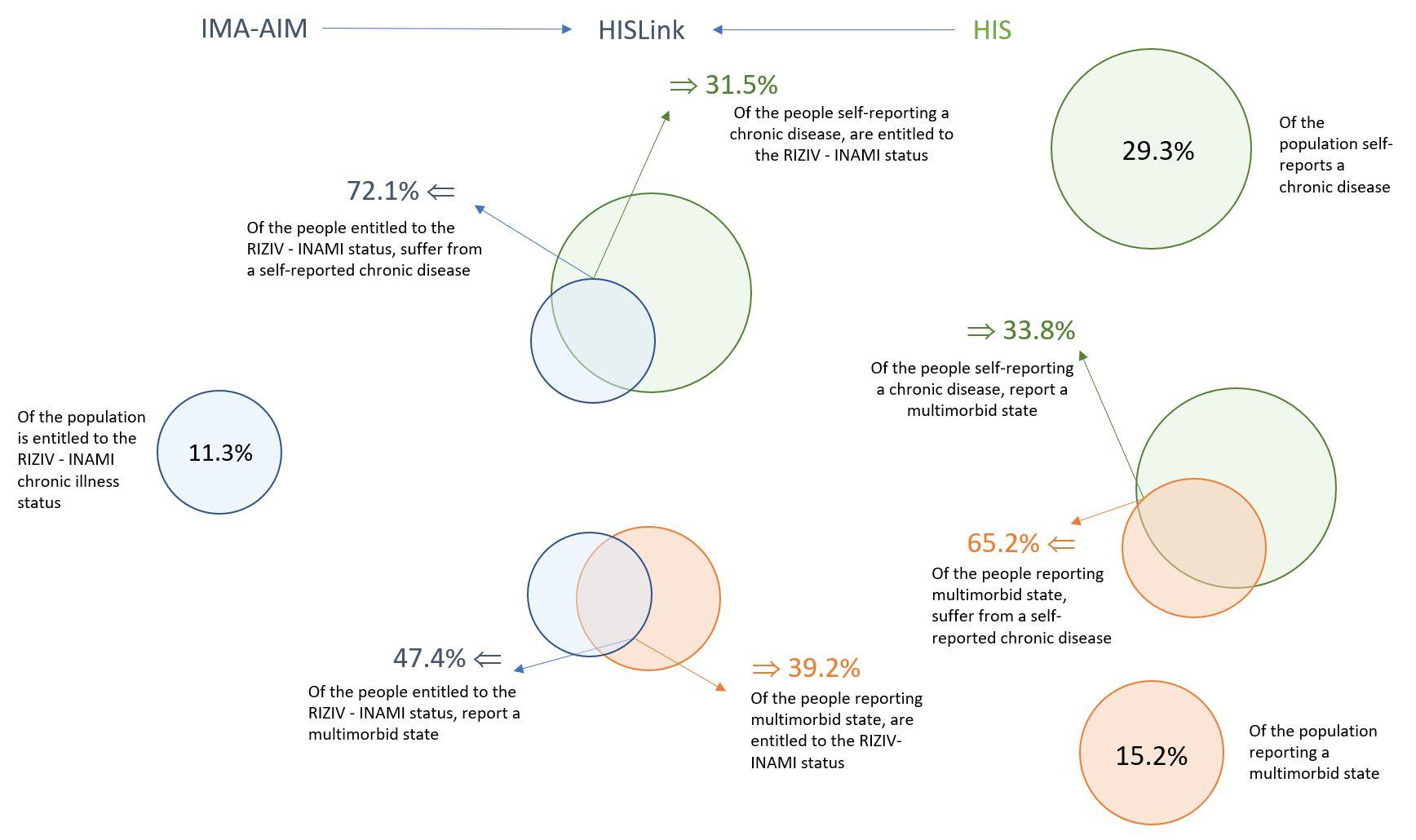

Comparison between CHR-1, CHR-2 and CHR-3

Although the three abovementioned indicators on the percentage of the population living with one or more chronic conditions all measure slightly different realities, we can expect a certain level of overlap. This is visualised in the figure below.

- In 2018, a little under one third (31.5%) of people with a self-declared chronic disease (HIS data) were also granted the RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status, but nearly three quarters (72.1%) of people with the status also self-identified as having a chronic disease.

- In 2018, 23.8% of Health Interview Survey respondents had either a self-declared chronic disease or the “chronic disease” status, but not both. This implies it is possible to obtain the official “chronic disease” status without self-identifying as chronically ill, but also to self-identify as chronically ill without being entitled to the corresponding status (which is a financial protection mechanism based essentially on financial criteria).

- Likewise, self-declared multimorbidity does not automatically come with the “chronic disease” status and vice-versa.

Perceived quality of life (QOL-1)

Nowadays, the goal of health care is not just to extend people’s life expectancy, but also to improve or at least try to maintain their health-related quality of life. This is all the more crucial in people with chronic conditions, who have to live with their health issue not just briefly, but for months and often even years. While quality of life is a somewhat subjective notion, a tool (EQ-5D-5L – you can find more information on the Belgian version in this KCE report) has been developed to measure it in an objective way through questions relating to mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.

Results

- In 2018, the average score for health-related quality of life was 0.843 – a decrease of 0.018 compared to 2013 (0.861). This trend was observed in all regions of Belgium, but it was strongest in Wallonia.

- People living with a chronic condition (based on self-declaration or RIZIV/INAMI status) reported a lower health-related quality of life than people with no chronic conditions. This trend was clearer in Wallonia and Brussels than in Flanders (in both 2013 and 2018).

- The gap in health-related quality of life between people with and without self-reported chronic conditions increased in Brussels and in Wallonia between 2013 and 2018, while it decreased in Flanders. The gap in health-related quality of life between people with and without chronic conditions based on RIZIV/INAMI status increased in Brussels, but decreased in Flanders and Wallonia.

- Quality of life was lower in people with an official RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status than in people with a self-declared chronic disease (in both 2013 and 2018).

- Quality of life was lower in people with a self-declared chronic disease who also had the official RIZIV/INAMI status than in those with only one of those indications of chronic disease.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Accessibility indicators

| Statut | Score | BE | Year | Fla | Wal | Bru | Source | UE15 (mean) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-2 Out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) as a share of total healthcare expenses* (%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 17.9 | 2016 | 18.7 | 17.1 | 15.9 | EU-SILC/ IMA-AIM |

/ | |||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | YES | C | 12.7 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 10.8 | ||||

| NO | C | 19.4 | 20.4 | 18.5 | 16.9 | |||||

| Self-reported chronic condition | YES | C | 15.1 | 15.7 | 14.7 | 13.6 | ||||

| NO | C | 19.7 | 20.6 | 18.8 | 17.4 | |||||

| A6 (ex-A-4) Self-reported unmet needs for medical examination due to financial reasons (% population aged 16+) | ||||||||||

| Total | 2.2 (1.4) |

2016 (2020) |

0.8 | 4.0 | 4.9 | EU-SILC/ IMA-AIM |

1.7 (0.9) |

|||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | YES | ⚠️3.9 | 2016 | 2.2 | 8.6 | 9.4 | / | |||

| NO | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 3.2 | ||||||

| Self-reported chronic condition | YES | ⚠️5.2 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 9.5 | |||||

| NO | 1.2 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 4.5 | ||||||

| A-4 (ex-EQ-4) Proportion of households with impoverishing or further impoverishing OOPs (%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 1.3 | 2016 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 4.3 | EU-SILC/ IMA-AIM |

/ | |||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | YES | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 5.9 | |||||

| NO | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 4.2 | ||||||

| Self-reported chronic condition | YES | ⚠️1.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 6.6 | |||||

| NO | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 2.7 | ||||||

| A-4 (ex-EQ-5) Proportion of households with catastrophic OOPs (%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 2.0 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 5.2 | EU-SILC/ IMA-AIM |

/ | ||||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | YES | ⚠️3.3 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 9.4 | |||||

| NO | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 4.8 | ||||||

| Self-reported chronic condition | YES | ⚠️2.9 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 8.5 | |||||

| NO | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 3.2 | ||||||

Share of out-of-pocket (OOP) payments in total healthcare expenses, in % (A-2)

Out-of-pocket (OOP) payments include co-payments, supplements (e.g. supplementary fees of non-conventioned physicians), as well as direct payments for products and services that are not reimbursed by the mandatory health insurance (over-the-counter drugs, glasses, etc.). These costs can be a financial barrier in access to care, particularly for people with limited resources or high care needs, which is often the case for those who suffer from a chronic disease.

In the spirit of our universal health insurance, one would expect that the share of OOPs in the total healthcare expenditure would be lower for people suffering from a chronic condition, with the aim to reduce the financial burden for those who with high and frequent needs of care. This indeed seems to be the case.

Results

- The overall share of OOPs in total healthcare expenses has remained stable at around 17-18% between 2008 and 2016. However, the share of co-payments in OOPs has decreased over time, while the share of supplements has increased.

- On average, the share of OOPs in total health expenditures is lower in households where at least one person has a chronic condition (between 12.7% and 15.1% vs about 19.5% in other households, depending on the data source). This is not really surprising, as those patients are more likely to be entitled to a lower yearly cap on their co-payments within the maximum billing system (MAB).

- The share of OOPs in total healthcare expenditures was also lower for financially vulnerable households, which can point either at effective financial protection measures or at the fact that those households are more likely to postpone or forego care for which they have to pay more themselves.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Link to technical datasheet and detailed results.

Percentage of households facing further impoverishing or catastrophic OOP expenses (A-4, ex-EQ-4 and EQ-5)

Households’ resources typically go first to basic needs such as food, housing and utilities, especially when money is tight. The amount that remains after those basic needs are covered is known as the “capacity to pay” (for health care). OOP payments are considered catastrophic when they exceed 40% of the capacity to pay, and impoverishing when they exceed this capacity to pay, even if the household is not poor to start with. In households that do not have the means to cover basic needs, any OOP payment for health care will make the situation worse and is therefore considered further impoverishing.

Results

- Households including a person with a self-reported chronic condition were more likely than others to experience impoverishing or further impoverishing out-of-pocket payments (1.7% vs 1.1% in the general population in 2016).

- Households including a person with a self-reported chronic condition were twice as likely as others to experience catastrophic OOPs (2.9% versus 1.4% in 2016).

- Catastrophic OOPs were also more likely for households including a person entitled to the RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status (see above under CHR-1).

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Percentage of people with self-reported unmet needs for medical examinations due to financial reasons (A-6, ex-A-4)

Results

- Individuals with a self-reported chronic condition are more likely than others to give up on necessary medical care because they cannot afford it.

- This percentage has increased over time, rising from 1.1% in 2008 to 5.2% in 2016 for people with a self-reported chronic condition and from 0.3% to 1.2% for those without.

- In 2016, people entitled to the “chronic disease” status were almost twice as likely as others to give up on necessary medical care for financial reasons (3.9% vs 2.0%).

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Quality – continuity indicators

| (ID) | Indicator | Status | Score | BE | Fla | Wal | Bru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informational continuity in general practice | |||||||

| QC-1 | Coverage of global medical record (% of persons who have a global medical record (GMR) with a general practitioner) | Total |  |

77.9 | 83.9 | 72.6 | 60.8 |

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status |  |

88.3 | 92.5 | 83.5 | 75.7 | ||

| No chronic illness status | NA | 77.3 | 83.3 | 71.8 | 60.0 | ||

| Informational continuity in medication | |||||||

| QC-7 NEW |

Proportion of individuals with a reference pharmacist (%) | Total | NA | 7.3 | 8.9 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status |  |

28.5 | 33.6 | 21.4 | 20.8 | ||

| No chronic illness status | NA | 4.6 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 2.5 | ||

| Management continuity between hospital and GP | |||||||

| QC-3 | Management continuity between hospital and GP | Total |  |

53.2 | 54.2 | 53.2 | 42.9 |

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status |  |

58.1 | 59.4 | 57.8 | 46.5 | ||

| No chronic illness status |  |

46.9 | 47.7 | 47.0 | 38.3 | ||

Percentage of the population who have a Global Medical Record (GMR) with their GP (QC-1)

Results

- Overall, GMR coverage is higher among people with a “chronic disease” status (88.3% in 2019, vs 77.3% in people not entitled to this status). This is particularly true in younger age groups; chronically ill older citizens, on the other hand, are less likely than their healthier peers to have a GMR with their GP.

- GMR coverage has been improving over the years, but less in people with a chronic disease (+12.6% between 2014 and 2019) than in others (+18.2%).

- GMR coverage remains slightly better in Flanders, but the gap with other regions is closing over time both for those with a chronic condition and for those without.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

GMR CHART

Percentage of patients with a reference pharmacist (QC-7)

The “reference pharmacist” concept was introduced in 2017 for customers of public pharmacies who need multiple treatments (with the exclusion of people in residential care or nursing homes). In theory, everyone is allowed to have a reference pharmacist, but this service is only reimbursed for chronic patients. The reference pharmacist ensures registration of all delivered medicines in an (electronic) pharmacy record, provides the patient with a medication scheme and makes this scheme available to other care providers.

Results

- At the end of 2019, two years after the introduction of the concept, 29% of people with the “chronic disease” status had a reference pharmacist. 57% were women.

- The coverage rate was substantially higher in Flanders than in Brussels and Wallonia.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Percentage of older people (aged 65 years or over) with a follow-up GP consultation within one week of hospital discharge (QC-3)

Results

- Despite the supposed benefits of a GP encounter within a week after leaving the hospital, the follow-up rate declined over time, from 65.2% in 2013 to 58.1% in 2019 among individuals with the “chronic disease” status and from 55.9% to 46.9% among those without the status.

- Although the decline is generalised, follow-up rates remain higher in individuals with the “chronic disease” status, suggesting those consultations are more likely to be offered to patients with the highest needs.

- For individuals with the “chronic disease” status, the follow-up rate was highest in Brussels and lowest in Wallonia in 2019.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Quality – people-centred care indicators

| Statut | Score | BE | Fla | Wal | Bru | UE-15 (mean) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QP-1 | Physician spending enough time with patients during the consultation (% of respondents, contact with GP/SP) | |||||||

| Total |  |

97.5 | 97.8 | 97.2 | 95.9 | 81.7 | ||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | Yes |  |

97.6 | 98.3 | 96.7 | 96.7 | - | |

| No |  |

97.4 | 97.7 | 97.2 | 95.9 | |||

| Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

97.4 | 98.0 | 96.9 | 96.5 | ||

| No |  |

97.6 | 98.0 | 97.4 | 95.4 | |||

| Chronic illness status & Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

98.2 | 98.6 | 98.3 | 95.6 | ||

| QP-3 | Physician giving opportunity to ask questions or raise concerns (% of respondents, contact with GP/SP) | |||||||

| Total |  |

97.5 | 98.0 | 97.0 | 95.9 | - | ||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | Yes |  |

96.6 | 98.3 | 96.6 | 96.7 | - | |

| No |  |

97.7 | 98.1 | 97.2 | 96.0 | |||

| Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

97.1 | 97.8 | 96.6 | 94.3 | ||

| No |  |

97.7 | 98.0 | 97.5 | 96.2 | |||

| Chronic illness status & Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

97.3 | 97.5 | 97.8 | 94.4 | ||

| QP-4 | Physician involving patients in decisions about care and/or treatments (% of respondents, contact with GP/SP) | |||||||

| Total |  |

95.4 | 96.0 | 94.8 | 93.8 | 82.8** | ||

| RIZIV-INAMI chronic illness status | Yes |  |

95.8 | 96.9 | 94.6 | 93.5 | - | |

| No |  |

95.4 | 95.8 | 94.8 | 94.1 | |||

| Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

94.3 | 95.1 | 93.6 | 91.8 | ||

| No |  |

96.1 | 96.6 | 95.8 | 94.1 | |||

| Chronic illness status & Self-reported chronic disease | Yes |  |

96.2 | 97.3 | 95.6 | 91.4 | ||

Patient experiences with the physician (QP-1, QP-3, QP-4)

These indicators are based on three questions included in the national Health Interview Survey (HIS), i.e.:

The last time you visited a physician (a general practitioner or a specialist),

- Did this doctor spend enough time with you? (QP-1)

- Did this doctor give you an opportunity to ask questions or raise concerns about recommended treatment? (QP-3)

- Did this doctor involve you as much as you wanted to be in the decisions about your care and treatment? (QP-4)

Results

- Patient experiences were largely positive (well over 90% of positive responses) for all three questions, regardless of age, region, and chronic disease status. Figures remained stable over time between 2013 and 2018 and were similar across regions, if slightly lower in Brussels.

- Overall, patients with a self-reported chronic condition and the RIZIV/INAMI status had a slightly more positive experience than those with either a self-reported chronic condition or the official status.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Preventive care

| Status | Score | BE | Fla | Wal | Bru | Source | EU-15 (mean) |

Target | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-4 | Influenza vaccination (% of population aged 65+) | |||||||||

| Total |  |

55,1 | 60,8 | 46,1 | 44,7 | IMA-AIM ; OECD | 53,7 | 75% (WHO) | ||

| Chronic illness status |  |

72,3 | 77,7 | 64,3 | 63,6 | |||||

| Not chronic illness status |  |

48,1 | 54,2 | 38,0 | 37,0 | |||||

| P-6 | Breast cancer screening (% women aged 50-69 years), organised screening | |||||||||

| Total |  |

33,2 | 50,2 | 4,7 | 10,4 | IMA-AIM | - | - | ||

| Chronic illness status |  |

28,2 | 45,6 | 4,7 | 12,0 | |||||

| Not chronic illness status |  |

33,0 | 50,9 | 4,7 | 10,0 | |||||

| P-7 | Breast cancer screening (% women aged 50-69 years), all mammograms | |||||||||

| Total |  |

59,7 | 65,3 | 51,5 | 51,0 | IMA-AIM | 73,5 | 75% (EU) | ||

| Chronic illness status |  |

58,8 | 63,0 | 53,2 | 55,5 | |||||

| Not chronic illness status |  |

59,9 | 65,7 | 51,1 | 50,0 | |||||

| P-11 | Regular contacts with dentist (% pop aged 3+) | |||||||||

| Total |  |

55,3 | 60,0 | 51,0 | 50,1 | IMA-AIM | - | |||

| Chronic illness status |  |

53,1 | 54,7 | 49,7 | 56,5 | |||||

| Not chronic illness status |  |

55,6 | 60,7 | 51,2 | 49,3 | |||||

Influenza vaccination among people aged 65 or older (P-4)

Results

- In 2019, the vaccination coverage for influenza among people aged 65 or older was higher in people with a RIZIV/INAMI “chronic disease” status (72.3%) than in those without this status (48.1%), regardless of socio-economic status.

- This gap in vaccination coverage between people with or without a chronic condition has been widening between 2013 (22.5%) and 2019 (24.2%).

- In 2019, influenza vaccination coverage for people with a “chronic disease” status was higher in Flanders (77.7%) than in Brussels (63.6%) or Wallonia (64.3%). This distribution was similar for non-chronic disease patients.

- In nursing homes in Brussels and Wallonia, residents with a “chronic disease” status were more often vaccinated (84.2%) than those without this status (73.9%).

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Breast cancer screening (P-6 and P-7)

Results

• In 2019, overall, participation in (organised) breast cancer screening was lower among women with the official “chronic disease” status (28.2%) than in women without this status (33.0%). The same held true for total screening coverage (58.8% vs 59.9%). However, figures varied depending on age group, access to increased reimbursement and region.

• Among women aged 50-59, participation in breast cancer screening (total coverage) was slightly higher in those with the “chronic disease” status than in those without.

• In Wallonia and in Brussels, participation in breast cancer screening (total coverage) was higher in women with the “chronic disease” status than in those without, regardless of age. In Flanders, it was lower.

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results

Percentage of the population having regular contacts with a dentist (P-11)

Results

- The percentage of the population with regular contacts with a dentist (at least two contacts in two different years over the last three years) has increased between 2014 and 2019, both in the general population (+5.5 percentage points) and in people with the “chronic disease” status (+9.7 percentage points).

- The overall regular dental attendance rate was lower among people with the “chronic disease” status than among people without this status. However, this lower rate can be entirely attributed to a lower attendance rate in the oldest age group (75+), which represents a significant fraction of people with the ’chronic illness status’. In all other age groups, people with a chronic condition had a better attendance rate.

- Regardless of “chronic disease” status, he highest regular attendance rate was registered among children and teenagers (aged 5-17), probably at least in part because dental care is fully reimbursed in this age group.

- In 2019, regular visits to the dentist were more common in Flanders (60.0%) than in Wallonia (51.0%) and in Brussels (50.1%). However, this difference was less obvious in people with the “chronic disease” status (56.5% in Brussels, 54.7% in Flanders and 49.7% in Wallonia).

Link to the technical sheet and detailed results